This is going to sound gruesome, but on Good Friday I touched my first dead body. To say I was nervous would be an understatement, but it felt like the right thing to do. It was in a clinical environment, but it was strangely moving. And the longer I was with the body, the more my apprehension gave way to fascination and respect.

Prof Sue Black, CAHID, University of Dundee

I was in Dundee University, in the new (2014) dissecting room in the Centre for Anatomy and Human Identification (CAHID). I was there to meet the Director of the centre, the Inverness born and bred Professor Sue Black OBE FRSC. Professor Black (‘for goodness sake, call me Sue!’) is a forensic anthropologist of world renown, and splits her time between teaching at the university and being a forensic practitioner, helping to identify human remains. In demand with everyone from murder squad detectives to the United Nations, her work is varied and important.

Sue’s work is often downright grizzly, but she manages to look beyond the horror that the rest of us would see. Because to allow herself to become emotionally involved would prevent her from remaining professional and forensic in her examination of a crime scene or of human remains, and that, she claims, would be useless. This professional detachment has been crucial in helping to bring the perpetrators of genocide to justice – we were talking the day after Radovan Karadzic, the “Butcher of Bosnia,” was sentenced to 40 years in prison for genocide in the 1990s. In addition to high profile international cases (she has also worked in Iraq, Kosovo and the aftermath of the Indian Ocean tsunami) Sue acts as an expert witness in murder trials and helps police and forensic pathologists to identify decomposed remains. Her work can give the families of missing loved ones the closure they so desperately need.

So how did a nice girl form the Highlands end up in such a gruesome profession? Through hard work and with the support of strong role models, it would seem. The first in her family to attend university, Sue was encouraged by her Glenelg granny (who died when she was 15) and by her biology teacher, Dr Archie Fraser from Inverness Royal Academy. A series of ‘being in the right place at the right time’ situations led Sue to her current position, a role she is both passionate about and feels privileged to undertake. And although she starred in both series of the hugely popular BBC ‘History Cold Cases’ she was uncomfortable with the fame it brought her, and with the necessary ‘dumbing down’ of the science in the name of prime time entertainment. ‘Never again’, she vows.

While the academic side of Sue’s life at CAHID is often interrupted by case work, she loves teaching, overseeing the work of 500 students at any one time. Teaching takes place partly in the dissecting room in which I was introduced to my first cadaver. The University receives about 80 donated bodies a year, which are embalmed with the revolutionary Thiel method, leaving them flexible and pliable, and far more like the live patients that doctors and surgeons will eventually be working on. It was in order to experience the ‘realism’ of this process that I was handed a pair of purple latex gloves and invited to flex the ankle and massage the calf muscle of a donated cadaver.

It took me a minute or so after putting on my gloves to touch the body, but Sue’s pragmatism (and that of her team) bolstered me, and I overcame my squeamishness. And I was struck by the respect with which all staff – student, mortuary staff, teaching and admin staff alike – treat the cadavers; they are genuinely viewed as the most precious of gifts, without which the teaching of the next generation of medics, forensic scientists and anatomists could not continue.

Sue Black is startlingly down to earth. She has been in the presence of literally thousands of dead bodies, and has never witnessed anything unusual, spiritual or paranormal around any of them.

‘But is death the end?’ I asked her. ‘Not if you believe in the value of education’, she replied. ‘The learning you gift to students by donating your body to medical science means your legacy could live on for a very long time indeed.’

your body to medical science means your legacy could live on for a very long time indeed.’

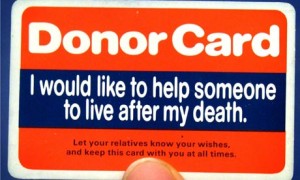

I hadn’t considered it before, but that does seem to be a logical next step. After all, I carry an organ donor card. If my organs can’t be used to help save a life when I die, maybe my body, if used for research or training, can do the next best thing. And if my body is shown the same respect as I witnessed on Good Friday, I’ll be in excellent hands.

This column first appeared in six SPP Group newspapers week ended 1st April 2016.

It’s good to share – and it’s easy, using the buttons below.