Bracing ourselves to step out of our hotel isn’t anything we had ever expected to do on holiday, but then we’d never been to Marrakech before. Seduced by tales of treasure-laden souks, the aroma of the spice market and the colours and culture of this corner of north west Africa, we had booked a few days away. Staying in a Riad, a traditional Moroccan merchant’s house built round a courtyard to escape the heat of the sun, seemed ‘the thing to do’. And it was imperative, I read, that our Riad should be within the walls of the Medina, Marrakech’s old walled city.

Bracing ourselves to step out of our hotel isn’t anything we had ever expected to do on holiday, but then we’d never been to Marrakech before. Seduced by tales of treasure-laden souks, the aroma of the spice market and the colours and culture of this corner of north west Africa, we had booked a few days away. Staying in a Riad, a traditional Moroccan merchant’s house built round a courtyard to escape the heat of the sun, seemed ‘the thing to do’. And it was imperative, I read, that our Riad should be within the walls of the Medina, Marrakech’s old walled city.

I chose one and booked an airport transfer, as we were told we’d otherwise get lost. The streets deep inside the Medina are too narrow for taxis, so transport included being met by a man with a handcart. He brushed away our efforts to help load our luggage, and we followed him through the maze of lanes, past shops piled high with beans and lentils, and others with just live chickens for sale.

Sunrise on the rooftop of Riad 72

Given our late arrival time we booked an in-house dinner. By 7am the following morning I was pacing the rooftop terrace, waiting for the sun to rise and for Mr Marr to stir. The call of the Imam from the mosque next door had woken me at 5, and I was itching to get out to explore.

It’s almost a cliché to describe Marrakech as an assault on the senses, but it’s accurate. It’s noisy, for a start. There are mopeds and bicycles everywhere, their motors, horns and bells ricocheting off the walls as they jostle for space in winding lanes with donkey-drawn carts, roadworks, and people walking, shouting, bartering and fighting. Five times a day there are calls to prayer; the mosques rarely synchronise, so the calls can last 15 minutes or more. And there are drums, and the flutes of the snake charmers and the calls of the women who paint henna tattoos.

Busy streets, the Medina in Marrakech

It’s hot and dusty too. Temperatures during our visit were unseasonably cool, but still hot enough to burn our skin – that which was exposed. We were respectful of the strict Muslim culture of a city which demands modesty of the tourists within its walls yet is happy to serve alcohol and offer hashish to keep them there – and spending – for

Spices on sale in the spice souk, Marrakech

longer.

The smells are overwhelming – stinking raw meat and the ‘pigeon poop’ and decay of the centuries-old tanning yards battling against the aromas of soaps and spices, fresh breads and sticky date-laden pastries being baked by the roadside.

And then there are people. Arms outstretched to entice you into their shops, try on their shoes, touch their silk scarves and feel the quality of their leather goods. Carpets and lampshades, toothpicks and mirrors, wooden camels, vials of kohl and crudely drawn pictures, all of it for sale, nothing with a price, and no way of assessing value, in the dim light and with all the fast-talking.

You would choose a purchase and it would be taken to the back of the shop to be wrapped – money would change hands and you’d later open the parcel to see you’d been given something lesser. Or you would haggle, seal the deal, and walk away pleased, only to realise you’d been arguing for the best part of ten minutes over the equivalent of 30p.

I lost count of the number of times we got lost or were scammed, the two usually went hand in hand. The streets of the Medina are laid out like the branches of a tree – main trunks, side branches, smaller branches, twigs, and finally leaves – all dead ends that never quite meet up again. Unlike on our usual travels where we seek out the path less trodden, in Marrakech, when we strayed too far from the tourist areas it did, occasionally, become intimidating.

It’s a lucrative pastime for young men to offer to take you to your destination for a fee – we were grateful to them when they offered that as a service. But more often than not they led us somewhere we didn’t want to go – their ‘uncle’s’ shop, or a ‘Berber Colour Festival’. By the time we realised we were being led a merry dance it was too late – we were deeper into the Medina. More than once we had to hand over cash to be allowed out of a shop or a dead end.

It’s a lucrative pastime for young men to offer to take you to your destination for a fee – we were grateful to them when they offered that as a service. But more often than not they led us somewhere we didn’t want to go – their ‘uncle’s’ shop, or a ‘Berber Colour Festival’. By the time we realised we were being led a merry dance it was too late – we were deeper into the Medina. More than once we had to hand over cash to be allowed out of a shop or a dead end.

Any yet…and yet. Some of the people we met were warm and kind, offering directions, advice and tastes of food that made us feel welcome. It was hard to know who to trust, but also difficult, the better we came to understand the city, to grudge the ‘entrepreneurship’ of some of the locals.

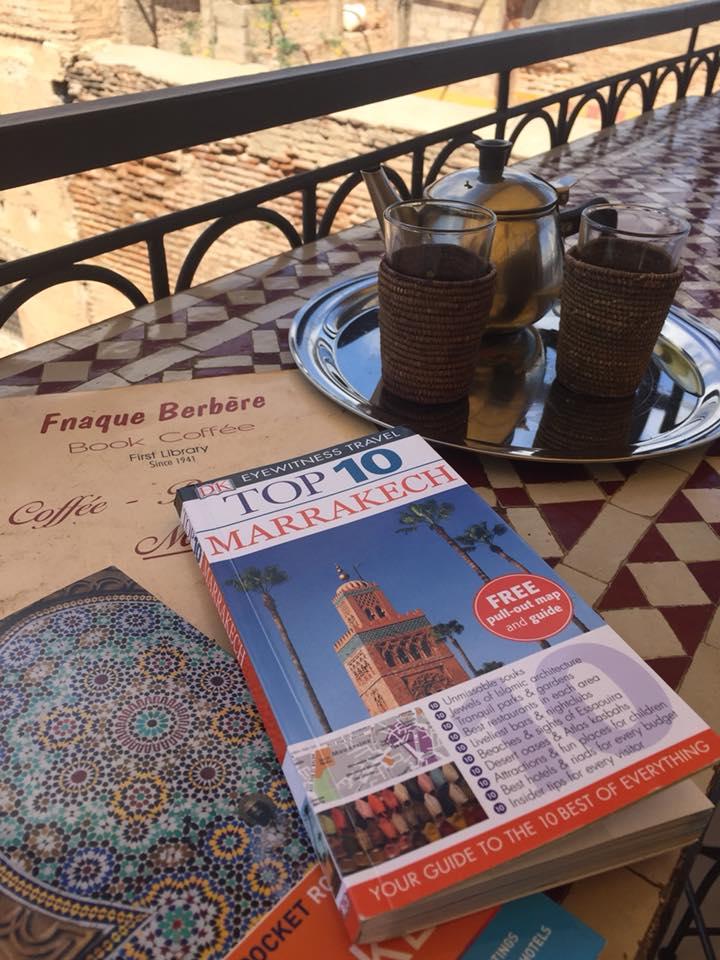

Morocco is a poor country, sharply divided between those who are extremely wealthy, and those who have – almost literally – nothing. A day’s wage in the fields is roughly the same as we paid for a cup of mint tea. Our Riad bill, with delicious dinners, wines, and an in-house hammam with massage thrown in, must have cost around an average annual wage. If we were scammed a little, or even a lot, I can’t worry too much – I think of it more as redressing the balance.

Marrakech was wonderful and dreadful, enchanting and exhausting, all at the same time. I am so glad to have visited. I’m not sure I’ll ever go back.