I’m not prone to being over-emotional – I rarely cry (except when watching The Sound of Music) but I was forced to dry my eyes while in Jersey for a couple of days last week. I was on a work trip, spending a couple of days there before writing an article for Connect, the magazine for Highlands and Islands Airports.

Our itinerary was suggested by Visit Jersey, but one thing was clear – we were determined to visit to the Jersey War Tunnels.

It was a gloriously sunny morning as we headed north with the car top down. Jersey is a small island – just nine miles by five, and it’s densely populated, with 103 000 souls mainly huddled together in and around the ‘capital’ of St Helier. But as we drove through leafy winding lanes, birds singing and spring flowers blooming, it felt more like rural France than Britain. Little wonder – we were only 14 miles from the French coast, yet 100 miles from England.

It was a gloriously sunny morning as we headed north with the car top down. Jersey is a small island – just nine miles by five, and it’s densely populated, with 103 000 souls mainly huddled together in and around the ‘capital’ of St Helier. But as we drove through leafy winding lanes, birds singing and spring flowers blooming, it felt more like rural France than Britain. Little wonder – we were only 14 miles from the French coast, yet 100 miles from England.

Arriving at the war tunnels we were asked if we’d brought jackets. The tunnels are chilling – and not just because they are underground. Advised that we’d spend about an hour and a half there we were surprised to emerge, blinking into the sunlight, to find that three hours had passed.

The Jersey War Tunnels were built by the Germans during World War Two – using forced and slave labour – as a secure underground munitions store. Later, fearing an allied invasion, they were turned into a military hospital. And while the very fabric of the museum is in itself significant, the stories which unfold along the kilometre of tunnels are even more poignant, bringing to life the dilemmas and struggles of the islanders who lived there during the long and dark years of German occupation.

The Jersey War Tunnels were built by the Germans during World War Two – using forced and slave labour – as a secure underground munitions store. Later, fearing an allied invasion, they were turned into a military hospital. And while the very fabric of the museum is in itself significant, the stories which unfold along the kilometre of tunnels are even more poignant, bringing to life the dilemmas and struggles of the islanders who lived there during the long and dark years of German occupation.

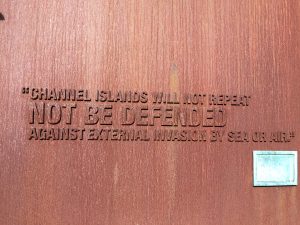

The goose bumps started even before we entered the tunnel mouth. In the sunshine outside are a collection of huge copper panels, each bearing a quote from a key player in the war. From Hitler was a desire to turn the islands into an impregnable fortress. From the Bailiff of Jersey, Alexander Coutanche, the noble sentiment ‘I will never leave and my wife will be by my side.’

And from Winston Churchill? You might expect something rousing, along the lines of ‘we will never surrender’. But no. The quote from Churchill was from a telegram: ‘Channel Islands will not, repeat not be defended against external invasion by sea or air.’ That telegram was sent on 19th June 1940, when the Germans were just days away. How must the islanders have felt?

And from Winston Churchill? You might expect something rousing, along the lines of ‘we will never surrender’. But no. The quote from Churchill was from a telegram: ‘Channel Islands will not, repeat not be defended against external invasion by sea or air.’ That telegram was sent on 19th June 1940, when the Germans were just days away. How must the islanders have felt?

Islanders were offered the option of evacuation to British mainland, but many chose to stay. Some, who had decided to leave, had hastily packed a few belongings but were turned away at the docks because of overcrowding on the requisitioned coal and cement ships. On returning home they found their homes had been ransacked; neighbours had taken their furniture, bikes, carpets and curtains. And so the mistrust between neighbours and friends began.

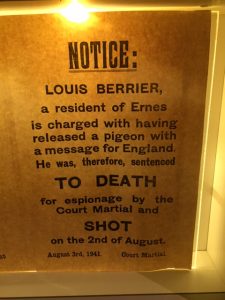

The exhibition was clear; life under German occupation was impossibly hard. Food was in desperately short supply, although some islanders did better than others – were they collaborating with the occupiers? Suspicion and lies became the norm, with neighbours encouraged to inform on each other to earn extra rations. What would you do if your children hadn’t eaten for days?

The exhibition was clear; life under German occupation was impossibly hard. Food was in desperately short supply, although some islanders did better than others – were they collaborating with the occupiers? Suspicion and lies became the norm, with neighbours encouraged to inform on each other to earn extra rations. What would you do if your children hadn’t eaten for days?

On entering the exhibition we were each given an identity card, relating to a real person who had lived in Jersey at the beginning of the occupation. Had they stayed on the island or been evacuated? Had they survived till Liberation Day? There were clues throughout the exhibition; the link to a real person brought the exhibition even more sharply to life. I was devastated to discover that my ‘character’ had been a Nazi informant – she had been the most notorious collaborator on the island and her actions were the cause of many islanders being imprisoned or killed. Imprisoned herself for her own safety on Liberation Day, she was sent on a mail boat to England and told never to return.

Chatting to the attendant on the desk as we left, I was told that the woman had lived a long and trouble-free life after the war. There was bitterness in the attendant’s voice, and I can’t blame her. In small communities such treacheries can’t easily be forgiven.

It took some time to process all that we’d seen; to process the sense of abandonment the islanders must have felt, and the darkness they lived through. That Jersey has managed, within the lifetime of my parents, to recover and become the carefree holiday destination and powerhouse of world finance that it is today, is both commendable and remarkable.

Holiday trips are time for kicking back and being carefree – we did that for the rest of our time on the island. The beaches are stunning, the cliff walks exhilarating and the food is divine; I am itching to get back. But the hours we spent in the Jersey War Tunnels will live with me for some time. As I said, I don’t cry easily.

Nicky Marr travelled to Jersey courtesy of Jersey Travel.

SUBSCRIBE to receive a weekly email with a link to my most recent column – just enter your email address in the wee widget onthe left hand side of my home page.

This column first appeared in six SPP Group newspapers week ended 14th April 2017.