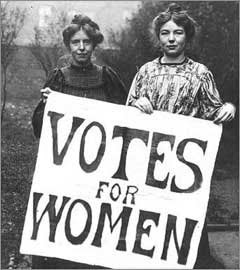

It is 100 years ago this week since Westminster passed the Representation of the People Act which, for the first time, allowed women the right to vote. This milestone is being marked with exhibitions and celebrations across the country, and statues are being unveiled to honour those women, both militant suffragettes and law-abiding suffragists, who campaigned and lobbied, sacrificed their freedom, and occasionally gave their lives, to gain this first rung on the ladder towards gender equality.

It is 100 years ago this week since Westminster passed the Representation of the People Act which, for the first time, allowed women the right to vote. This milestone is being marked with exhibitions and celebrations across the country, and statues are being unveiled to honour those women, both militant suffragettes and law-abiding suffragists, who campaigned and lobbied, sacrificed their freedom, and occasionally gave their lives, to gain this first rung on the ladder towards gender equality.

The 1918 Act was a start, but it didn’t go terribly far. Only women over 30 were allowed to vote, and even then there were restrictions. They could only vote if they owned property, or were married to a man who did, or if they were, or had been, at university. That meant that the vast majority of the country’s women – 60% – remained disenfranchised.

Holding MPs back from granting women equal voting rights was the widely held belief that on the whole, women were too feeble minded or hysterical to make important decisions. But there was more; granting the vote to all women would have given them an electoral majority. In addition to the slightly higher proportion of women than men that naturally occurs across the population the country was still at war; 700,000 British soldiers had been killed, and many were still abroad.

The position for women was improved a decade later when The Equal Franchise Act of 1928 extended the right to vote to all women over 21. But the right to vote, although a good first step, hasn’t got us even close to gender equality.

An EU league table of where member states lie in terms of gender equality shows that Britain has made little or no progress in this regard in the past decade. Only a quarter of board chairs, presidents and chief executives in the UK are women. In 2016 there were six women who were CEOs of FTSE 100 companies; there were eight men called David.

An EU league table of where member states lie in terms of gender equality shows that Britain has made little or no progress in this regard in the past decade. Only a quarter of board chairs, presidents and chief executives in the UK are women. In 2016 there were six women who were CEOs of FTSE 100 companies; there were eight men called David.

The BBC gender pay gap has been in the headlines recently, with Channel 4 journalist Cathy Newman staging a sit-in at the BBC until she was promised answers, and a few high profile BBC journalists offering to take a pay cut. But that is just the tip of the iceberg. According to the World Economic Forum’s annual report on the gender gap published in November, women only earn a mean monthly salary that’s 66 per cent that of their male counterparts.

And there’s more. A staggering 57 per cent of all the work that UK women do is unpaid, which is almost double the 32 per cent that men do. Unpaid work here relates to housework, cooking, shopping and caring for dependents. In bearing the brunt of the burden of the unpaid work that every family needs to have happen, many women simply don’t have enough hours in the day to pursue their careers. So it’s little wonder that so many work part time or take career breaks, and find when they do return to full time employment that they are overlooked for promotions.

And there’s more. A staggering 57 per cent of all the work that UK women do is unpaid, which is almost double the 32 per cent that men do. Unpaid work here relates to housework, cooking, shopping and caring for dependents. In bearing the brunt of the burden of the unpaid work that every family needs to have happen, many women simply don’t have enough hours in the day to pursue their careers. So it’s little wonder that so many work part time or take career breaks, and find when they do return to full time employment that they are overlooked for promotions.

The problem doesn’t just exist when a family has young children, as women find themselves bearing the burden of caring for elderly relatives too. And the implications are felt beyond just monthly earnings. Many women find themselves facing pension poverty in later life because they have not made full pension contributions.

So what can be done? Will our elected representatives help? Well you might think that having a woman at the helm of the country would be a bonus, but there’s scant evidence of that happening, especially with the current (and seemingly endless) distractions of Brexit.

And even if all our female MPs and MSPs got together in cross party groups to try and make a difference, they’d still be outnumbered. 208 female MPs were elected at the 2017 General Election, making that 32% of all MPs and a record high, but still not enough to make a big enough difference. North of the border we are faring marginally better, with a 35% representation in Holyrood.

Is it that fewer women than men are standing for election? I wouldn’t be surprised – it’s hardly a life or a job that appeals to me. Could it be the adversarial style of government that we have here that is putting women off? Or could it be the restrictions imposed by party politics? The incompatibility of political life with family life might play some part in the decision of some women to steer clear of wanting to stand…it may be a surprise to learn that there is no provision for MPs to have parental leave – either maternity or paternity -although there is provision for MSPs in Scotland.

It is right that we mark 100 years since women were first given the vote in the UK – after all, we did get there before women in Switzerland, who didn’t get the vote till 1971. But while women have made great progress in the last century, the fight for equality is far from over.